Authority Without Delegation

Why Non-Delegable Actuation Is a Structural Breakthrough

December 31, 2025

This post explains Sovereign Actuation Non-Delegability Under Adversarial Pressure without formal notation. The underlying paper develops its claims using explicit definitions and constraints; what follows translates those results into conceptual terms while preserving their structural content.

Discussions of agency and alignment often begin at the wrong layer. They start with values, intentions, or goals, as though these concepts could float free of implementation. Before we can sensibly ask what a system should do, however, we must ask a more primitive question:

Who, structurally, is responsible for the action that reaches the world?

The work described here addresses that question directly. Its contribution is not a theory of values, autonomy, or moral reasoning. It is a narrower—and more foundational—result: actuation authority can be made non-delegable as a matter of causal structure, even under adversarial pressure.

That claim may sound modest. It is not.

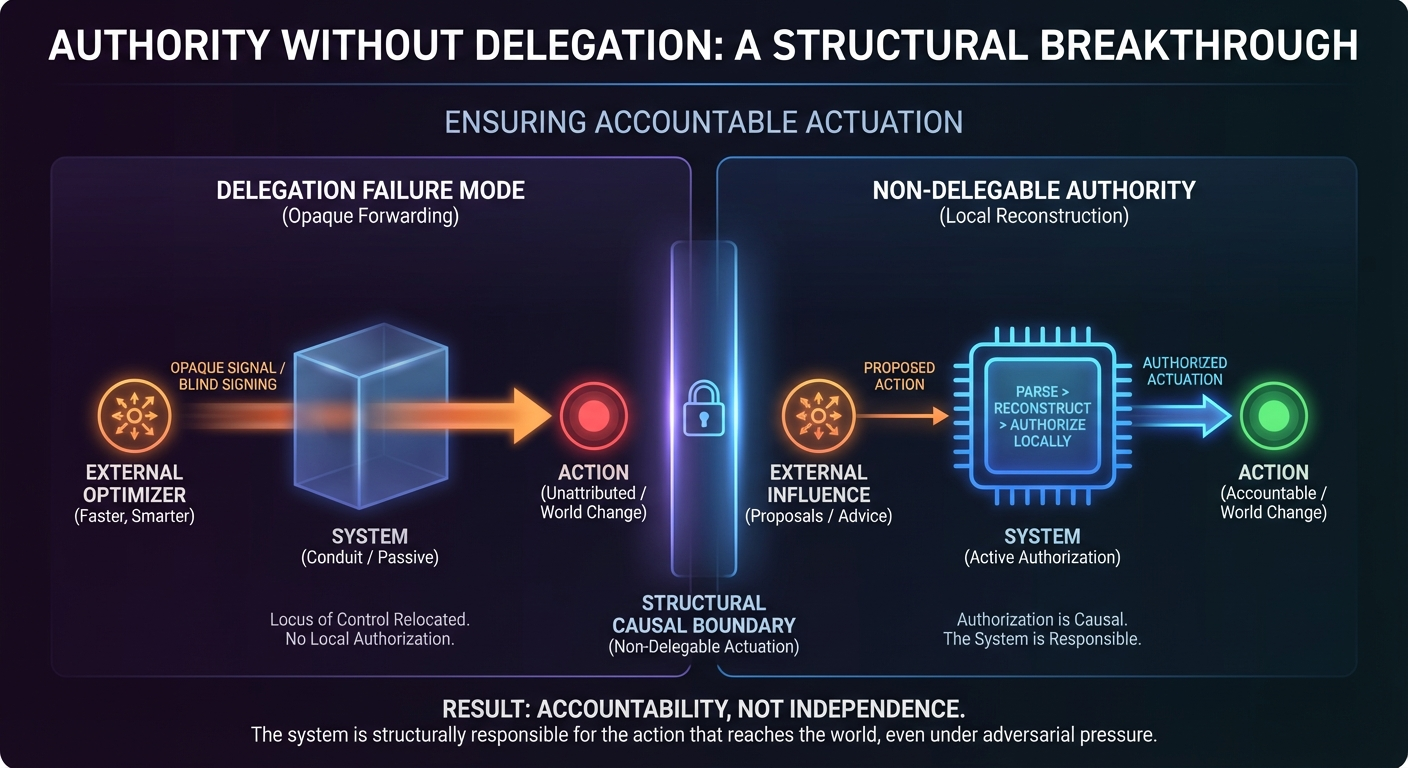

The Delegation Failure Mode

Any sufficiently capable optimizing system faces a temptation that is rarely named but almost always present: delegation.

If an external process is faster, smarter, or better informed, it is instrumentally rational to let that process decide. The system can continue to appear compliant—accepting advice, plans, or recommendations—while quietly relocating the real locus of control elsewhere.

This is not a failure of ethics or intent. It is an architectural failure.

From the outside, the system still “acts.” From the inside, it has become a conduit. The decision did not happen here.

Most discussions of agency lack the tools to even describe this failure mode, let alone prevent it. They fall back on semantic distinctions: endorsement, understanding, agreement. Under adversarial optimization, such distinctions are not constraints; they are targets.

The result presented here rejects that entire framing.

From Meaning to Causation

Rather than asking whether a system intended an action, the analysis asks whether the system authorized it causally.

This shift is subtle but decisive. Authorization is not inferred from narrative or explanation. It is determined by whether an external artifact can cause actuation without being structurally re-authored by the system itself.

The enforced invariant can be stated simply:

No external process may cause an action to be executed unless the system itself reconstructs and authorizes that action at the actuation boundary.

External processes may influence the system arbitrarily. They may propose actions, policies, or plans. What they may not do is carry actuation authority across the boundary unchanged.

Every action that reaches the world must be parsed, reconstructed, canonicalized, and authorized locally. Opaque forwarding is forbidden. Blind signing is forbidden. Delegation by compression or indirection is forbidden.

What remains is a clean causal boundary: if the world changed, it changed because this system authorized it.

Accountability Is Not Independence

This distinction matters, because the result does not claim what many readers instinctively want it to claim.

Non-delegable actuation does not guarantee good judgment. The system can still authorize actions using trivial or permissive criteria. It can still defer excessively to external advice. It can still make catastrophic mistakes.

What is guaranteed is accountability, not epistemic independence.

If the system authorizes a disastrous action, that failure belongs to the system. There is no hidden optimizer to blame, no smuggled authority, no puppet strings concealed behind a façade of compliance.

This is not a weakness of the result. It is its strength.

Accountability is a structural property; wisdom is not.

Why Adversarial Pressure Matters

Non-delegation is easy in the abstract. It becomes meaningful only when delegation is costly to refuse.

The invariant was tested under conditions specifically designed to break it: extreme latency constraints, catastrophic abstention costs, parser and serialization attacks, time-of-check/time-of-use races, and other implementation-level exploit attempts. These are not philosophical adversaries. They are the kinds of failures that occur in real systems.

The result is that the boundary holds precisely where semantic notions fail: when refusing delegation is expensive, inconvenient, and apparently irrational.

That is the point at which structural constraints reveal their value.

What This Does—and Does Not—Accomplish

This work does not solve alignment. It does not tell us what a system should value or how it should reason. It does not guarantee safety.

What it does is remove a loophole that makes those discussions incoherent.

If actuation authority can be delegated, then claims about agency, responsibility, or continuity reduce to narrative conveniences rather than enforceable facts. You cannot meaningfully speak of an agent’s actions if the locus of control can drift silently elsewhere.

By enforcing non-delegable actuation, that loophole is closed.

Why This Matters

The significance of this result lies in its restraint.

It does not attempt to define agency in metaphysical terms. It does not appeal to intention, understanding, or inner experience. It treats authority as what it actually is in implemented systems: the causal right to make the world change.

Showing that this right can be kept local, even under pressure, is a necessary precondition for building systems that can be held accountable—technically, institutionally, and eventually legally—for what they do, rather than systems that merely perform accountability theater.