Echoes of Freud

How Psychoanalysis Rewired Western Culture

December 28, 2025

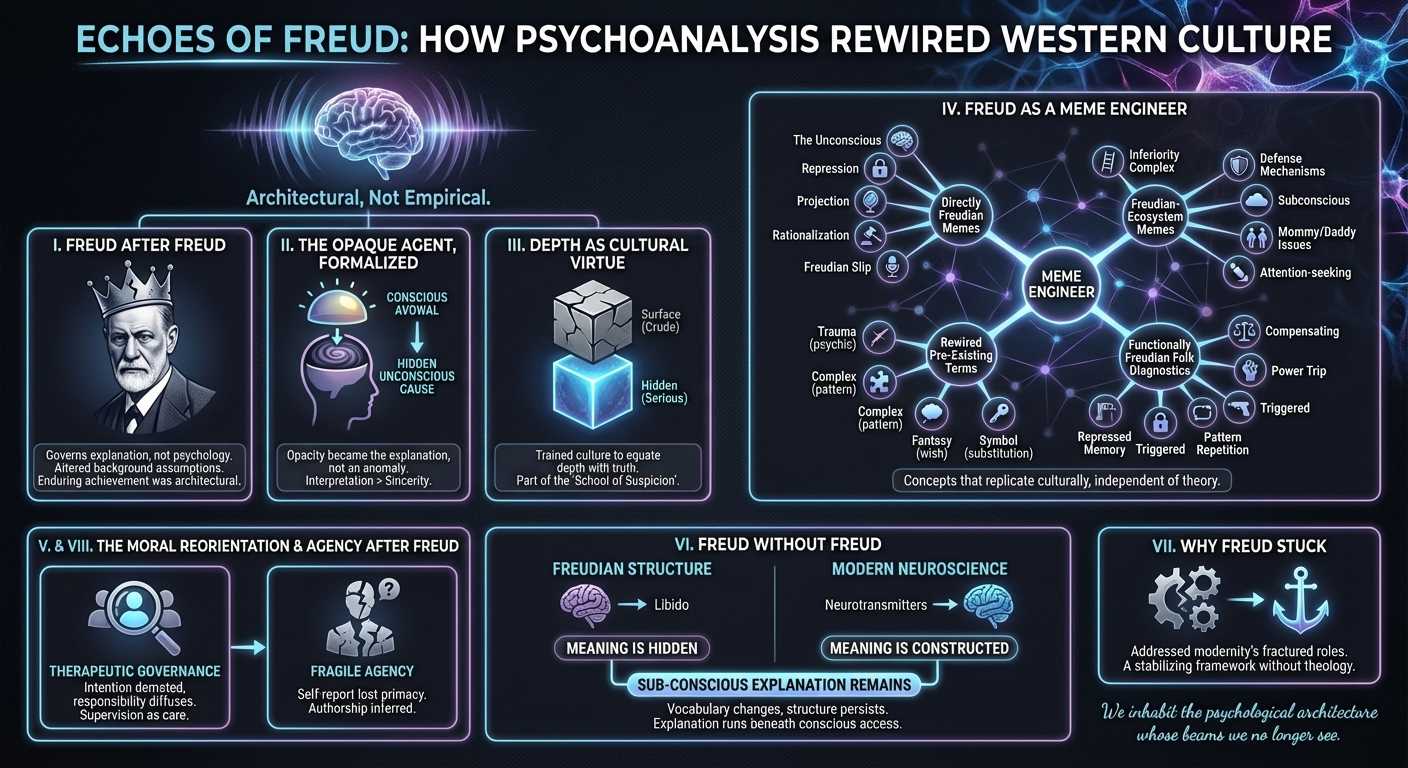

I. Freud After Freud

Freud no longer governs psychology, yet he governs explanation.

In contemporary Western culture it is routine to disavow psychoanalysis while continuing to reason through its categories. Few people defend the libido theory, fewer still the metapsychology of drives, and almost no one takes the clinical practice of couch analysis as a serious scientific method. None of this is decisive. Freud’s enduring achievement was architectural rather than empirical. He altered the background assumptions under which human behavior is interpreted, judged, excused, and governed.

Sigmund Freud survives less as a theorist than as an unacknowledged legislator of common sense. Western culture continues to inhabit the conceptual space he carved, even while insisting it has moved beyond him.

II. The Opaque Agent, Formalized

Long before Freud, Western thought already contained suspicions about the transparency of the agent. Augustine described a will divided against itself. Hume doubted the sovereignty of reason over passion. Novelists such as Dostoevsky explored compulsions that eluded conscious control. The hidden self was not a novelty.

What Freud changed was not the existence of opacity, but its status. Earlier traditions treated self-division as moral failure, theological corruption, or tragic exception. Freud transformed it into a standing explanatory default. The gap between avowal and cause became systematic rather than episodic, medical rather than moral, general rather than exceptional.

After Freud, opacity ceased to be an anomaly requiring explanation. It became the explanation.

Behavior came to be understood as the surface trace of deeper processes operating outside conscious access and often against declared intention. Testimony lost its decisiveness. Sincerity lost evidentiary force. Interpretation took precedence over avowal, and with it arose a new form of authority: the authority of those trained to see beneath the surface.

III. Depth as Cultural Virtue

This posture has become so natural that it rarely announces itself. Modern discourse assumes, almost without reflection, that people project, repress, rationalize, compensate, and repeat patterns whose origins lie elsewhere than where they point. Political outbursts invite diagnosis. Moral failures invite backstory. Disagreements invite speculation about unacknowledged motives.

These moves feel sophisticated because Freud trained the culture to equate depth with truth. Surface explanations register as crude; hidden explanations register as serious. This aesthetic preference survives regardless of whether Freud’s specific mechanisms are accepted. The form of explanation remains Freudian even when its contents are replaced.

Freud belongs here alongside Marx and Nietzsche, later grouped by Paul Ricoeur as the school of suspicion. Marx taught us to distrust institutions. Nietzsche taught us to distrust values. Freud taught us to distrust our own explanations. That intimacy explains the reach and durability of psychoanalytic thought.

IV. Freud as a Meme Engineer

Freud was not merely a theorist; he was one of the most successful creators of memes in intellectual history. His ideas survived not because they were empirically dominant, but because they were linguistically compact, cognitively efficient, and socially powerful. They traveled well. They attached themselves to ordinary speech. They granted explanatory leverage to anyone who could deploy them.

What follows is not a taxonomy of psychoanalysis, but an inventory of memes—conceptual units that replicate culturally, independent of their original theoretical scaffolding.

Directly Freudian Memes

These concepts were coined or canonized by Freud himself, and their everyday usage descends cleanly from his work, even when flattened or vulgarized.

The unconscious — hidden mental causation beneath awareness

Repression — motivated forgetting rather than accident

Projection — attributing one’s own motives or traits to others

Rationalization — post-hoc justification presented as reason

Freudian slip — error treated as revelation

Narcissism / Narcissist — self-directed psychic investment

Ego — the mediating self-structure

Ego-driven / Ego-centric — popular derivatives of ego theory

Fixation — developmental arrest with adult consequences

Anal-retentive — control as personality residue

Oral fixation — dependency translated into habit

Acting out — behavior as discharge rather than deliberation

Denial — refusal of acknowledgment

Talk therapy — speech as a privileged causal surface

Depth psychology — truth located beneath articulation

Each compresses a causal story into a single word. To invoke one is to assert depth without narrating a theory.

Freudian-Ecosystem Memes

These did not originate with Freud personally, but they are intelligible only because he built the conceptual environment in which they could function.

Inferiority complex — Alfred Adler

Compensation — Adlerian in origin, culturally merged with Freud

Defense mechanisms — systematized by Anna Freud

Subconscious — popularized despite Freud later rejecting it

Mommy issues / Daddy issues — vulgarized family-dynamic shorthand

Attention-seeking — motivational suspicion framing

Ego maniac — journalistic hybrid of ego theory and pathology

Attribution here is often wrong in textbooks and conversation alike, which itself testifies to Freud’s gravitational pull. He built the stage on which others’ ideas became legible.

Rewired Pre-Existing Terms

Some words predate Freud, but their meanings were permanently altered by his framework. The older senses survive only as historical footnotes.

Trauma — from physical wound to persistent psychic injury

Complex — from generic adjective to structured mental pattern

Fantasy — from imagination to wish-fulfillment

Symbol — from literary device to unconscious substitution

These terms now carry psychoanalytic assumptions even when used by speakers who would reject psychoanalysis outright.

Functionally Freudian Folk Diagnostics

These are not technical terms at all, yet they operate exactly as Freudian memes. They function as compressed causal accusations in everyday moral and social discourse.

Compensating

Power trip

Triggered

Repressed memory

Unresolved issues

Pattern repetition

To deploy one is to claim hidden motive, deny surface explanation, and assert interpretive authority in a single move.

Taken together, these lists show why Freud’s influence long outlived his theories. He did not merely propose explanations; he seeded language with replicators. Once embedded, they no longer required psychoanalysis to survive.

V. The Moral Reorientation

When intention is demoted, responsibility diffuses.

Action is increasingly understood through formative history, psychological constraint, and structural influence. This diffusion supports compassion, often appropriately. It also licenses supervision. If agents cannot reliably understand their own motives, guidance and correction acquire a benevolent sheen. The subject becomes legible to experts in a way the subject is no longer legible to themselves.

Modern bureaucratic paternalism, therapeutic governance, and soft social coercion draw much of their plausibility from this Freudian reorientation. Once self-understanding is treated as suspect, oversight presents itself as care rather than control.

VI. Freud Without Freud: Persistence Through Substitution

Freud’s deeper success lies in how thoroughly this sensibility survived the abandonment of his specific theories. Libido gives way to neurotransmitters. Repression yields to avoidance circuitry. Complexes are redescribed as schemas. The vocabulary changes; the structure remains.

Contemporary neuroscience diverges sharply from Freud in its metaphysics. Where Freud believed meaning was hidden, neuroscience often suggests that meaning is constructed retrospectively. Drives become circuits; conflicts become activations; interpretation gives way to correlation. Yet the cultural posture remains strikingly similar. Explanation still runs beneath conscious access. Testimony is downgraded. Authority flows toward those who can see what the subject cannot.

The disagreement concerns what lies beneath awareness, not whether something does.

VII. Why Freud Stuck

This persistence was no accident. Freud addressed a coordination problem generated by modernity itself. Industrial society fractured roles, compressed communities, intensified status competition, and stripped traditional moral narratives of credibility without replacing them. People experienced themselves as divided and opaque, driven by impulses they neither endorsed nor understood.

Freud offered a framework that preserved determinism without despair, meaning without theology, critique without revolution. Psychoanalysis functioned as a secular confessional in which interpretation replaced absolution and expertise replaced priesthood. Cultures do not discard frameworks that perform this stabilizing work. They absorb them.

VIII. Agency After Freud

From the perspective of agency-preserving frameworks—those concerned with authorship, responsibility, and self-reference—the inheritance Freud left is precise and costly.

He installed a default model of the agent as internally fragmented, partially opaque, and interpretively subordinate. Self-report lost primacy. Authorship became something inferred rather than asserted. Harm no longer required intent. Authority followed explanatory depth.

This model does not destroy agency, but it renders it fragile. Preserving agency now requires explicit reconstruction rather than passive inheritance. It is no longer the background assumption of explanation.

Postscript

Freud does not persist because he was right. He persists because he taught a civilization how to explain itself. His concepts rewired intuition, his vocabulary colonized judgment, and his suspicions became defaults. We continue to inhabit a psychological architecture whose beams we no longer see, even as we renovate its rooms. To understand Freud now is to recognize the shape of the house we still live in.