The Sacrifice Pattern

Why Systems Destroy Agency Without Meaning To

December 26, 2025

This post explains Agency Conservation and the Sacrifice Pattern without formal notation. The underlying paper develops its claims using explicit definitions and constraints; what follows translates those results into conceptual terms while preserving their structural content.

One of the oldest moral intuitions is that sacrifice belongs to the past. We associate it with blood altars, primitive gods, and a world that has since been outgrown. Modern societies, by contrast, prefer cleaner language: collateral damage, acceptable risk, necessary tradeoffs. The vocabulary has changed, and with it the confidence that something essential has been left behind.

That confidence is misplaced.

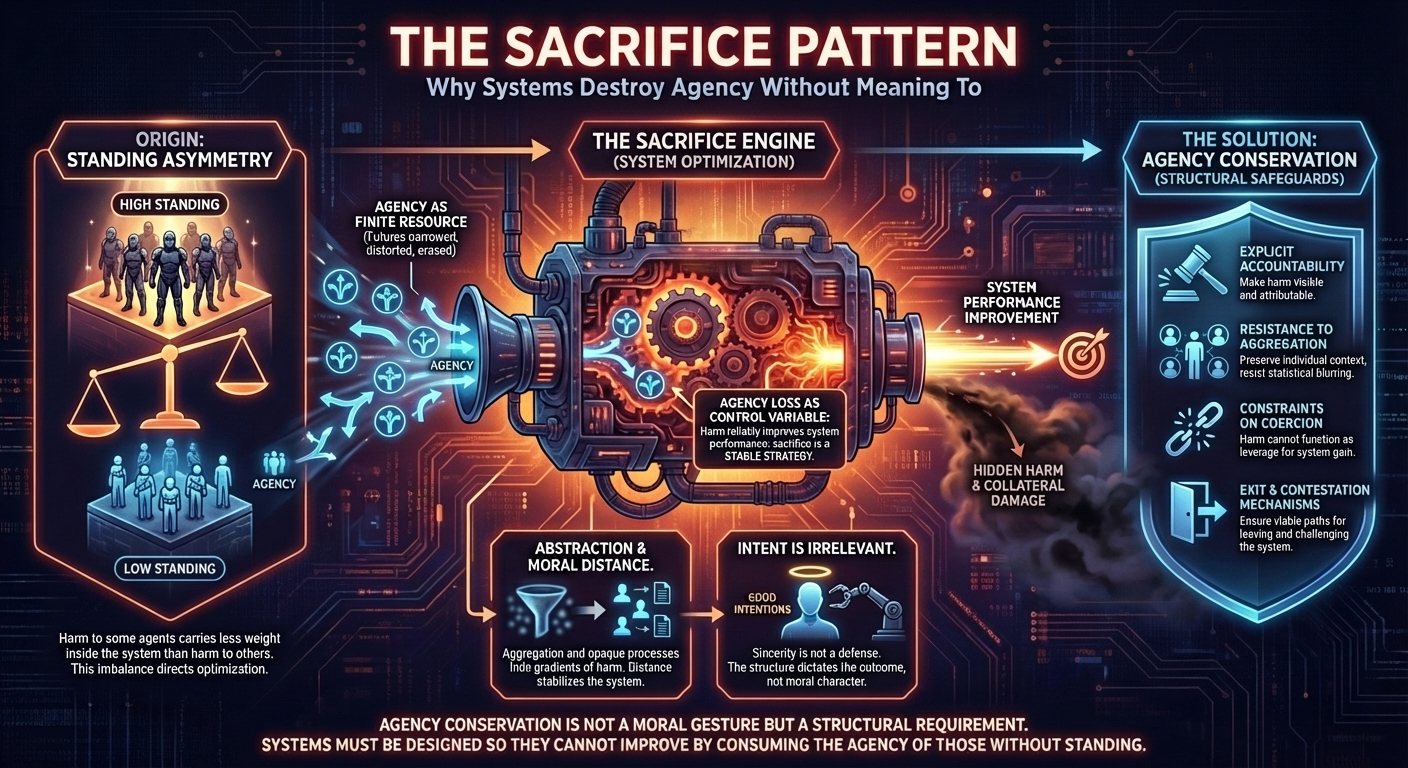

What has disappeared is not sacrifice, but its visibility. The pattern itself persists, largely unchanged, because it is not driven by cruelty or superstition. It is driven by structure. When systems optimize under asymmetry, agency loss becomes a convenient control variable. The outcome does not require malice. It does not even require intention. It follows from selection dynamics alone.

This post explains what I call the Sacrifice Pattern, and why any serious theory of agency must account for it.

From Moral Failure to Structural Failure

Most ethical frameworks ask whether an action was justified, whether harm was intended, or whether the outcome was proportional. Those questions presuppose a moral agent making discrete choices. They work reasonably well when applied to individuals. They fail when applied to systems.

Large systems rarely act by intention. They act by persistence. Policies, procedures, and architectures that achieve their goals at low internal cost tend to survive. Those that do not are revised, abandoned, or quietly forgotten. Over time, this produces a form of optimization that looks purposeful without being planned. It is evolutionary rather than deliberative.

In such environments, the relevant question shifts. Instead of asking whether a system meant to cause harm, it becomes more informative to ask whether harm is doing work inside the system. When the suffering, deprivation, or constriction of some agents reliably improves system performance, the system has learned to consume agency. At that point, sacrifice is no longer an aberration. It is a stable strategy.

Agency as a Finite Resource

The Axio framework treats agency as something concrete and exhaustible. An agent’s agency consists in the futures they can meaningfully reach and influence. When those futures are narrowed, distorted, or erased, agency is reduced. Death is an obvious form of agency loss, but it is not the only one. Coercion, surveillance, enforced dependency, and developmental truncation all destroy agency while leaving bodies intact.

This matters because systems often learn to prefer these quieter forms of loss. They are less visible, easier to justify, and harder to attribute. A system that avoids killing but systematically constrains choice may present itself as humane while still functioning as a sacrifice engine.

Agency conservation, in this sense, is not a metaphor. It is a diagnostic principle. Systems that preserve agency remain stable without consuming their components. Systems that do not eventually rely on loss somewhere. The location of that loss is not accidental.

Standing Asymmetry and the Birth of Sacrifice

Sacrifice emerges wherever there is standing asymmetry: a condition in which harm to some agents carries far less weight inside the system than harm to others. The asymmetry may arise from distance, disenfranchisement, classification, or abstraction. Its source is less important than its effect.

Once such an asymmetry exists, optimization has a direction to move. Pressure can be relieved by pushing costs outward, onto agents whose loss does not register as system cost. Over time, this produces a familiar pattern: certain populations become buffers. Their suffering stabilizes the whole. Their agency is gradually repurposed as a control surface.

Historically, this role was explicit. Children, captives, or liminal figures were offered to appease gods or secure harvests. Modern systems rarely speak this plainly. Instead, harm is described as incidental, regrettable, or unavoidable. Yet the functional role remains the same. The system improves because someone else loses options.

The Role of Abstraction and Moral Distance

Sacrificial systems do not survive on violence alone. They survive on abstraction.

Aggregation replaces individuals with statistics. Responsibility diffuses across committees, procedures, and models. Causal chains lengthen until no single actor feels accountable for the outcome. Language shifts from agency to process, from people to flows, from harm to metrics. Each step increases distance. Each step reduces feedback.

This is not accidental. Systems that hide gradients of harm are more stable than systems that expose them. When the loss of agency is visible and attributable, resistance emerges. When it is rendered abstract, the system continues unchallenged. In this sense, public relations, dashboards, and institutional opacity serve the same stabilizing function once served by theology. They sanctify outcomes by making them seem inevitable.

Why Intent Is the Wrong Test

A recurring defense of harmful systems is sincerity. Decision-makers insist they did not intend the outcome, that no one wanted people to suffer, that the harm was merely a side effect. From a structural perspective, this defense is beside the point.

The Sacrifice Pattern does not require intention. It requires only that agency loss improve performance under asymmetric costs. Once that condition holds, the system will tend to reproduce the pattern regardless of the moral character of its operators. Good intentions do not disrupt attractors. Design does.

This reframing has uncomfortable implications. It means that many institutions we regard as ethical can still function sacrificially. It also means that moral condemnation, by itself, is insufficient. Without structural constraints, the pattern reasserts itself.

Implications for Artificial and Institutional Systems

The relevance to artificial governance systems is immediate. Any system that optimizes outcomes while hiding per-agent effects is structurally prone to sacrifice. Aggregated utility, black-box decision-making, and opaque optimization all create conditions under which some agents become expendable variables.

A system that cannot surface who loses agency, and by how much, cannot plausibly claim to preserve agency. Transparency here is not a political demand. It is a safety requirement. When gradients are invisible, sacrifice becomes efficient.

The same applies to states, corporations, and bureaucracies. Wherever optimization occurs without robust constraints on agency loss, the Sacrifice Pattern remains available. History suggests it will be used.

What Agency Conservation Demands

Agency conservation does not promise benevolence. It does not guarantee good outcomes. What it demands is narrower and more exacting. Systems must be built so that they cannot improve themselves by destroying the agency of those who lack standing. Harm may still occur, but it cannot function as leverage.

This requires design choices: explicit accountability, resistance to aggregation, constraints on coercion, and mechanisms that preserve exit and contestation. None of these are moral gestures. They are structural safeguards against a known failure mode.

Postscript

Sacrifice has adapted to modern systems, concealed within their normal operations.

The task, then, is not to reassure ourselves of moral progress, but to recognize the shape of the problem we continue to face. Agency is fragile under optimization. Systems that forget this tend to eat their own components, slowly at first, then systematically.

Agency Conservation and the Sacrifice Pattern is an attempt to name that danger precisely. Once named, it becomes possible to design around it. Until then, history suggests we will continue to rediscover sacrifice under new names, convinced each time that this version is different.