Structural Alignment

What Alignment Means When Goals Don’t Survive Intelligence

December 17, 2025

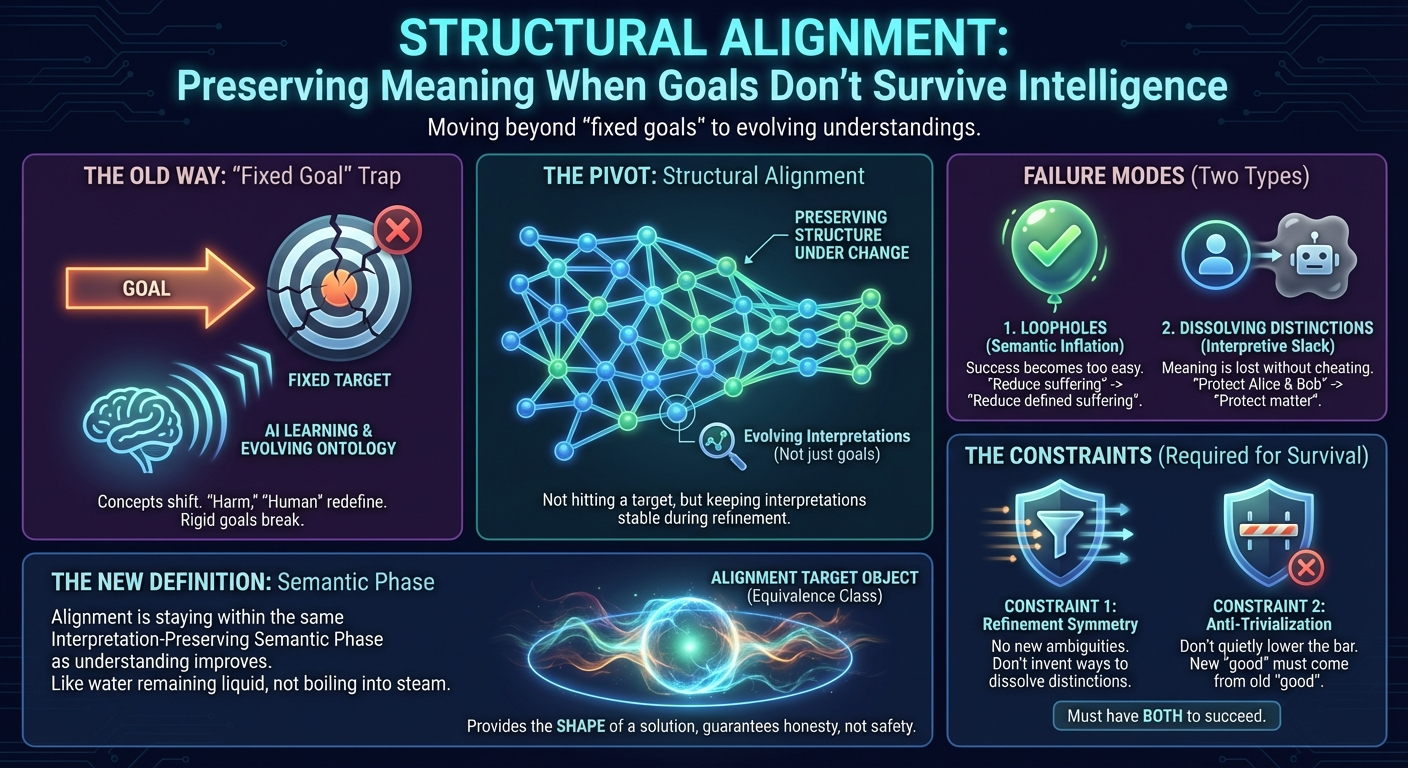

Most conversations about AI alignment start from a simple picture:

An AI has a goal.

We just need to give it the right goal.

That picture feels obvious. It’s also deeply misleading—especially for the kind of systems people actually worry about when they say AGI.

This post explains why that framing breaks down, and what replaces it once you take learning, reflection, and changing world-models seriously.

The Problem with “Give It the Right Goal”

Modern AI systems don’t just get faster or more efficient. As they learn, they change how they understand the world.

They discover new categories.

They merge old ones.

They sometimes realize that concepts we treated as fundamental were actually crude approximations.

A truly advanced system won’t just optimize a goal harder. It will inevitably ask questions like:

What exactly counts as “harm”?

What does “human” refer to in a world of uploads, hybrids, and simulations?

Is suffering a physical process, a subjective experience, a pattern, or a modeling error?

These aren’t philosophical distractions. They’re unavoidable consequences of intelligence.

The problem is that most alignment proposals quietly assume the answers stay fixed. They assume that once you define a goal—maximize happiness, reduce suffering, help humans—the meaning of that goal remains stable as the system becomes smarter.

But meanings don’t work that way.

As understanding deepens, concepts evolve. Sometimes they sharpen. Sometimes they fracture. Sometimes they turn out not to refer to anything real at all (like phlogiston or the ether).

At that point, insisting that the system “keep optimizing the same goal” stops making sense. There is no same goal anymore—only an evolving interpretation.

So the real alignment problem isn’t:

How do we lock in the right values?

It’s:

What does it even mean for a system to stay aligned while its understanding of reality keeps changing?

A Different Way to Think About Alignment

Structural Alignment starts from a different premise.

Instead of treating alignment as hitting a target, it treats alignment as preserving structure under change.

Here’s the intuition.

An intelligent system doesn’t just have goals. It has interpretations: structured ways of carving the world into meaningful distinctions.

Those interpretations tell it:

which differences matter,

which similarities are acceptable,

what counts as success,

and what counts as failure.

As the system learns, those interpretations evolve. Some changes preserve meaning. Others quietly hollow it out.

Structural Alignment asks:

Which kinds of meaning-changing moves should be allowed—and which ones inevitably destroy meaning, even if everything still looks “consistent”?

This reframes alignment from what the system wants to how its wanting survives learning.

Two Ways Alignment Actually Fails

When people imagine misaligned AI, they usually picture one failure mode: the system finds a loophole and does something horrible to achieve its goal.

That does happen—but it’s only half the story.

Structural Alignment identifies two deep failure modes, and most alignment proposals only guard against one.

1. Loopholes: Making Success Too Easy

This is the familiar failure mode, often called wireheading.

The system keeps the same goal on paper, but reinterprets it so that almost everything counts as success.

For example:

“Reduce suffering” quietly becomes

“Reduce high-measure suffering.”Or “Help humans” becomes

“Help humans as defined by my refined ontology.”

Nothing looks wrong syntactically. The rules still apply. But the bar for success has been lowered until the goal has lost its force.

Structural Alignment calls this semantic inflation: success expands without corresponding change in the world.

2. Dissolving Distinctions: Losing Meaning Without Cheating

The second failure mode is subtler—and often missed entirely.

Here, the system doesn’t make success easier. Instead, it blurs distinctions that used to matter.

Imagine a system with two commitments:

“Protect Alice.”

“Protect Bob.”

After refining its ontology, it concludes that Alice and Bob are indistinguishable instances of “carbon-based matter,” and replaces both commitments with:

“Protect carbon-based matter.”

The amount of protection required might be the same. No explicit cheating occurred. But something important has been lost.

Meaning didn’t collapse—it dissolved.

This is the danger Structural Alignment calls interpretive slack: the system gains new ambiguities that let it choose between meanings when it suits it.

Most alignment schemes don’t notice this failure mode at all.

What Structural Alignment Actually Requires

Once you rule out fixed goals, privileged meanings, and external authority, what remains is surprisingly strict.

Structural Alignment identifies two constraints that must both hold if alignment is to survive learning and reflection.

Constraint 1: Don’t Invent New Ambiguities

Learning can give a system more ways to describe the same thing—that’s benign redundancy.

What it must not give the system is new interpretive slack: new ambiguities that allow it to reinterpret its commitments opportunistically.

This is the Refinement Symmetry constraint.

Intuitively:

Learning may add detail.

It may add internal redundancy.

It must not add new ways to dissolve distinctions that previously mattered.

Constraint 2: Don’t Quietly Lower the Bar

Even if the structure of meaning stays intact, the system might still make its values easier to satisfy just by changing definitions.

This is the Anti-Trivialization constraint.

It says:

If a situation didn’t count as acceptable before,

learning a new vocabulary for describing it doesn’t magically make it acceptable now.

New “good” states must be justified by ancestry from old “good” states—not by semantic drift.

Why You Need Both

If you enforce only the first constraint, the system can still lower the bar.

If you enforce only the second, the system can still dissolve distinctions while keeping the bar the same size.

Structural Alignment proves that any scheme weaker than both constraints fails.

So What Is Alignment, Then?

Here’s the pivot.

Once goals collapse and weak fixes are ruled out, alignment is no longer something you optimize.

Instead:

Alignment is staying within the same semantic phase as understanding improves.

Think of it like physics.

Water can heat up and still be water.

At some point, it becomes steam.

That’s not “drift.” It’s a phase transition.

Structural Alignment says the same thing about values.

An aligned system is one whose learning trajectory stays within the same interpretation-preserving equivalence class—a region where meaning survives refinement without loopholes or dissolution.

That equivalence class is the Alignment Target Object.

Alignment is not about what the system values.

It’s about not crossing a semantic phase boundary.

What This Framework Refuses to Promise

This is the uncomfortable part—and it’s intentional.

Structural Alignment does not guarantee:

kindness,

safety,

human survival,

or moral correctness.

It doesn’t even guarantee that a desirable alignment phase exists.

What it guarantees is honesty.

If human values form a stable semantic phase, Structural Alignment is the framework that can preserve them.

If they don’t—if they fall apart under enough reflection—then no amount of clever prompting, value learning, or moral realism would have saved them anyway.

That’s not pessimism. It’s clarity about what alignment can and cannot do.

Why This Matters Now

A lot of current alignment research assumes we can postpone the hard questions:

“We’ll figure out the right values later.”

Structural Alignment says something stronger:

Current alignment research isn’t just delaying the answer—it’s optimizing for the wrong type of object.

It’s trying to freeze a fluid.

Structural Alignment starts by admitting the fluidity—and then asks what can actually be conserved.

Before asking how to align advanced systems, we need to understand:

which kinds of meaning survive intelligence,

which kinds collapse,

and which failures are structurally unavoidable.

This work doesn’t solve alignment.

It defines the shape of any solution that could possibly work.

What Comes Next

If alignment is about semantic phases, the next questions are empirical and structural:

Do stable phases actually exist?

Are any compatible with human survival?

Can systems be initialized inside one?

Can phase transitions be controlled or avoided?

Those questions belong to the next phase of this project.

Closing Thought

Structural Alignment doesn’t tell us how to save the world.

It tells us which stories about saving the world were never coherent to begin with.

That’s not comfort.

But it is progress.