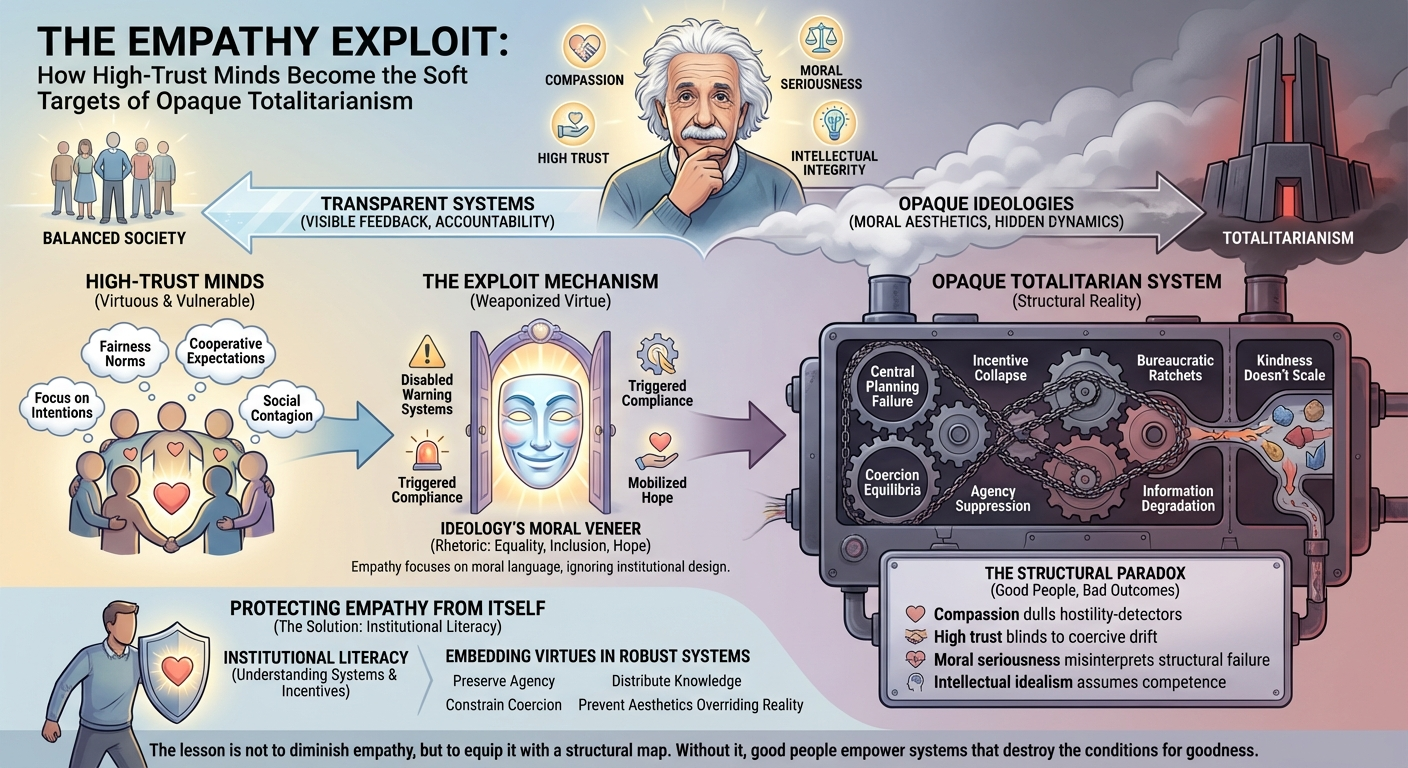

The Empathy Exploit

How High-Trust Minds Become the Soft Targets of Opaque Totalitarianism

November 27, 2025

The tragedy of Einstein’s political innocence illustrates a deeper structural truth: the most dangerous ideologies are the ones that weaponize our best traits. Compassion, high trust, moral seriousness, and intellectual integrity—virtues that make a civilization humane—can be turned into vulnerabilities when the ideology’s stated aims diverge radically from its structural dynamics.

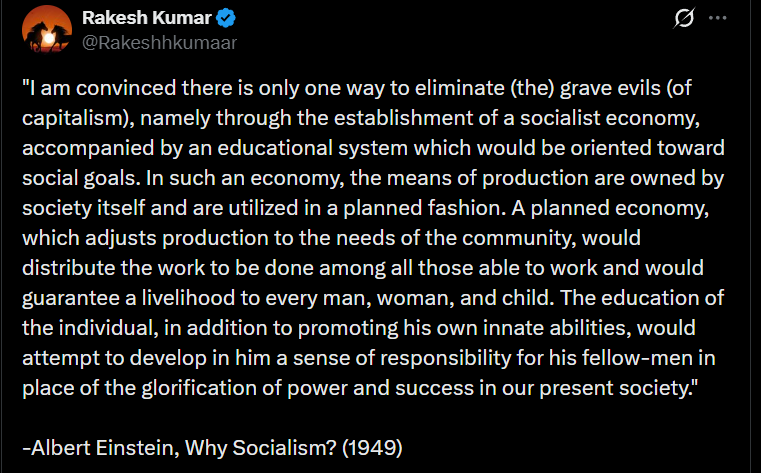

Einstein endorsed socialism in 1949 not because he was naïve about human suffering, but because he was exquisitely sensitive to it. He recoiled from fascism, from militarism, from the psychopathic power politics of his era. His moral radar was functioning. What failed was not his conscience, but his model of how institutions behave under concentrated power and distorted incentives. He assumed benevolent planners could do what real-world planners never can: allocate resources without suppressing agency, distribute knowledge without collapsing information quality, and wield coercion without becoming addicted to it.

This is the Empathy Exploit: opaque authoritarian ideologies recruit their defenders from the ranks of the decent.: opaque authoritarian systems conscript the virtuous first, because moral trust is the easiest resource to metabolize into power.: opaque authoritarian systems recruit their defenders from the very people whose moral instincts are strongest.**: opaque authoritarian ideologies recruit their defenders from the ranks of the decent.

1. The Attack Surface of Virtue

High-trust populations—those with strong fairness norms, high empathy, and cooperative expectations—are acutely vulnerable to systems that present themselves in morally aesthetic terms. Socialism declares itself the ideology of inclusion, equality, shared purpose, and the abolition of suffering. This moral veneer disables early-warning systems that would otherwise detect coercive drift.

An ideology that signals cruelty activates defensive cognition. An ideology that signals compassion triggers compliance. This is the structural asymmetry Einstein exemplifies: he saw a moral horizon, not an institutional failure mode. And this blindness is predictable among people who value cooperation over conflict and reason over domination.

2. When Empathy Meets Incentive Failure

The failure mode of socialism does not emerge from its rhetoric but from its architecture. Central planning annihilates the distributed incentives that generate knowledge, align action, and protect individual agency. But these dynamics are invisible at the level of moral language. They belong to the domain of institutional design, not emotional resonance.

Empathic minds do not instinctively model tacit knowledge, emergent coordination, bureaucratic ratchets, coercion equilibria, or incentive‑compatible failure modes. They reason about intentions. And intentions are the camouflage layer.

This is why opaque authoritarian systems outperform transparent ones in recruitment: they outsource their moral justification to the people least prepared to see the structural trap.

3. The Recruiting Power of High-Trust Minds

Empathy is socially contagious. When figures like Einstein endorse an ideology, they export their moral legitimacy along with it. The appearance of decency becomes a vector for the spread of a system that, once instantiated, rapidly consumes the freedoms that made such decency possible in the first place.

This is not merely an intellectual error or a historical curiosity; it is an evolutionary vulnerability. High-trust populations produce more moral capital than low-trust populations, and opaque totalitarian ideologies parasitize that surplus. They grow by metabolizing sincerity.

The propaganda of transparent tyrannies depends on fear. The propaganda of opaque tyrannies depends on hope. Fear mobilizes resistance. Hope mobilizes compliance.

4. The Structural Paradox: Good People Enable Bad Systems

Here is the uncomfortable conclusion: the very traits that make individuals admirable can make societies fragile.

Compassion dulls hostility-detectors.

High trust blinds you to coercive drift.

Moral seriousness misinterprets structural failure as moral sabotage.

Intellectual idealism assumes competence where none exists.

Opaque authoritarianism does not begin by attacking the wicked. It begins by conscripting the virtuous. It requires moral legitimacy to gain political leverage. Once leverage is secured, coercion becomes inevitable. Once coercion is normalized, agency collapses. And once agency collapses, atrocity becomes a predictable selection pressure.

Einstein’s mistake was not kindness. It was the assumption that kindness scales. It does not.

5. The Empathy Exploit in Contemporary Form

The same pattern repeats wherever an ideology advertises moral salvation without confronting the constraints of coordination, economic calculation, and human incentives. High-trust populations remain the primary resource for these systems, because trust can be transmuted into power faster than suspicion can be.

Opaque authoritarianism does not spread through bullies. It spreads through caregivers.

This is why the Empathy Exploit matters: it reveals why some of the worst outcomes in modern history were enabled not by sadists, but by idealists.

Conclusion: Protecting Empathy from Itself

Empathy is not the enemy. But empathy without institutional literacy becomes a liability. The way to immunize high-trust populations is not to diminish trust, compassion, or fairness, but to embed them in systems that preserve agency, distribute knowledge, constrain coercion, and prevent moral aesthetics from overriding structural reality.

Einstein was not a political idiot. He was a moral idealist navigating an opaque landscape with an incomplete map. That mistake is forgivable. The lesson is not.

A civilization that fails to understand the Empathy Exploit will repeat the same pattern: good people empowering systems that eventually destroy the conditions that make goodness possible.