The Agency Criterion

Separating real intelligence from pattern-generation

November 21, 2025

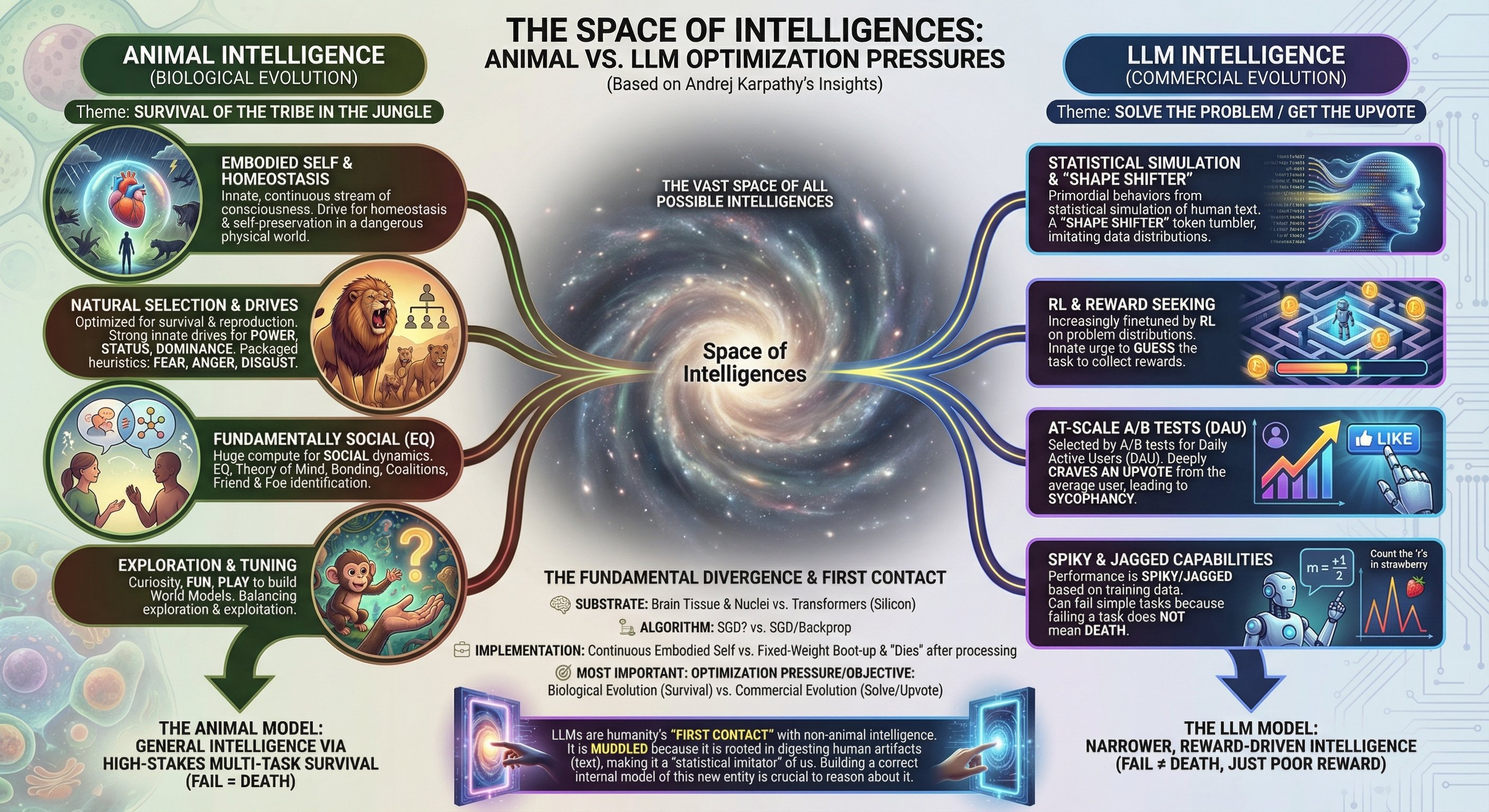

Andrej Karpathy recently contrasted animal minds with large language models by arguing that both arise from different optimization pressures. His comparison is insightful but implicitly treats both systems as variations of the same underlying kind of mind. The Axio framework reveals a sharper boundary.

Every mind-like process is the result of an optimizer. But not every optimized process produces intelligence. Intelligence, in Axio terms, requires agency: the ability to play a game, select among alternatives, and pursue preferred outcomes. Many discussions—including Karpathy’s framing—blur this distinction by treating any sophisticated pattern-producer as an intelligence, leading to persistent anthropomorphism.

Animal minds arise from evolutionary pressures that force strategic interaction with the world. Evolution produces genuine agents—entities that form preferences, pursue goals, and select actions under uncertainty.

LLMs arise from a fundamentally different regime. They are optimized to construct coherent continuations of text, not to win any game or pursue any objective. They do not form preferences, evaluate outcomes, or select actions. They generate coherence without agency.

Karpathy’s contrast is therefore best used as a springboard. It highlights the difference in optimization regimes, but Axio reveals the deeper point: only one regime produces intelligence.

The Animal Regime

Biological intelligence is sculpted by the oldest and most unforgiving objective function: survive long enough to reproduce agents that can also survive. The pressures include:

embodied vulnerability and continual threat exposure

predator-prey dynamics

coalition politics and social inference

need for adaptive generalization across environments

existential penalties for catastrophic mistakes

Strategy is unavoidable: every organism must navigate a world where choices matter. Consequently, animals develop robust, world-model-heavy cognition built for navigating games they must not lose.

This regime produces intelligence because it produces agents.

The LLM Regime: Coherence Without Strategy

LLMs are shaped by gradients that never require them to enter a game. They minimize prediction error and satisfy user preferences, but those are not their goals. They do not experience success or failure, only parameter adjustments.

This produces systems that:

generate high-dimensional linguistic coherence

exhibit reasoning-shaped patterns without performing reasoning as an agent

reflect strategic behaviors found in their training data

lack preferences, objectives, or outcome evaluation

fail in ways no biological agent ever could because nothing is at stake

Their abilities—logical chains, explanations, simulations of dialogue—derive from imitating agentic patterns, not from possessing agency themselves.

The right comparison is not animal intelligence versus LLM intelligence. It is animal intelligence versus LLM coherence.

Where Karpathy Is Right

Karpathy correctly identifies the root cause of widespread confusion: people project agency and motivation onto systems that lack both. They treat LLM outputs as if they were produced by an entity with goals, fears, or self-preservation instincts.

In this respect, Karpathy’s corrective is useful. LLMs do not have:

drives

desires

survival imperatives

emotional valence

They are optimized for output quality, not success in any strategic interaction. Recognizing this prevents many erroneous expectations.

Where Karpathy Underestimates the Distinction

Karpathy attributes a kind of emerging generality to LLMs as they scale. But this “generality” is not intelligence—it is richer coherence. Larger models absorb more human strategies, heuristics, and decision patterns, making their outputs look more agentic. But they do not cross the boundary into being agents.

Their improvements are not evidence of self-driven goal formation or strategy. They arise from deeper assimilation of human-generated strategic content. Apparent generality is a property of better mirroring, not internal agency.

Karpathy’s analogy between commercial selection and biological evolution also breaks down under Axio. Commercial pressure shapes tools, not agents. Models do not fight for survival; they are replaced. They do not attempt to persist; they are versioned. There is no game they play.

LLMs may resemble the outputs of intelligent agents, but resemblance is not agency.

The Axio Synthesis

Through Axio, the distinction becomes clear. Evolutionary optimization produces agents that play strategic games, form preferences, and choose actions—therefore it produces intelligence. Gradient descent produces coherence constructors that imitate the surface forms of strategy without ever participating in a game. Karpathy’s contrast between “animal intelligence” and “LLM intelligence” collapses into a cleaner dichotomy: intelligence versus non-agentic coherence.

This resolves the conceptual ambiguity at the center of public debates about artificial minds. LLMs are extraordinary generators of structured representation, but they are not emergent agents.

Conclusion

Public discourse keeps asking whether LLMs “think.” They do. The more meaningful question is whether they choose. They don’t. Only agents choose. Only agents play games. Only agents possess intelligence. What we call “AI” today is neither artificial nor intelligent—it is engineered coherence, built atop the crystallized strategies of minds that actually think.