Prometheus in Print

How the Printing Press Foretold the Internet

November 13, 2025

Introduction

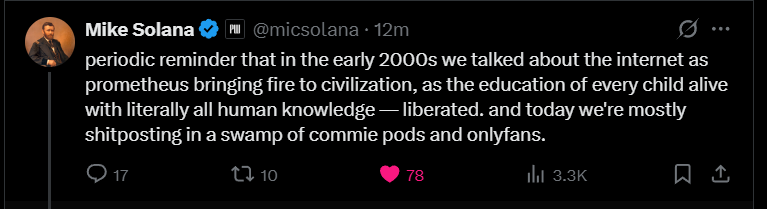

Mike Solana’s lament about the internet’s fall from early-2000s techno-utopianism into a morass of low-grade discourse is familiar—not because the internet failed uniquely, but because every information technology follows the same arc. Gutenberg’s printing press is the strongest historical parallel. Its trajectory illustrates a fundamental pattern in the evolution of media: the release of a transformative technology produces cultural shockwaves that the surrounding society cannot immediately metabolize.

The printing press did not democratize wisdom. It democratized everything, including human vulgarity. The internet merely repeated the pattern at higher bandwidth.

1. The Utopian Dawn: Printing as Civilization’s New Fire

When Gutenberg’s movable type began its spread in the late 15th century, European humanists spoke in the same Promethean tones that internet evangelists would later adopt.

Books would become abundant and cheap.

Knowledge would ascend from monasteries into the public square.

Literacy would rise, ignorance would wither.

Scripture and classical learning would percolate into every household.

Cardinal Turrecremata called it “the divine art”. Ulrich Zell declared it “the invention of inventions”. Erasmus imagined a world in which even the poor could acquire the books that once required princely wealth.

This rhetoric is indistinguishable from the early internet ethos—“every child alive with access to all human knowledge”. The printing press, like the web, was heralded as nothing less than an epistemic liberation engine.

2. The Reality: Pamphlets, Polemics, and Pornography

The idealism did not survive contact with the market.

Within a generation, the most printed categories were not the classics or the sacred texts, but:

political pamphlets and agitprop

apocalyptic predictions

scurrilous theological attacks

astrology guides

miracle tales and superstition manuals

sex stories and bawdy plays

forged revelations and sensational hoaxes

The Protestant Reformation—and its bloody aftermath—was impossible without rapid-fire print propaganda. Peasant uprisings leveraged pamphleteering instead of sermons. The average “viral” product of the press was not humanist scholarship, but the 16th-century equivalent of a meme coded in satire, fear, or outrage.

Humanists dreamed of a republic of letters; they got an economy of pamphlet wars.

3. The Moral Panic: “The Multitude Is Intoxicated”

Predictably, elites panicked.

“Books pour forth without moderation and without discrimination.”

“Errors spread faster than the truth can refute them.”

“This new technology corrupts the masses with falsehoods.”

“The world is full of madmen who now print their ravings.”

This was the 16th-century version of claims about internet misinformation, attention collapse, low-quality discourse, and the “death of expertise.” The complaints are structurally identical.

4. The Regulatory Reflex: Licensing, Censorship, Indexes

Governments and churches responded with familiar tactics:

mandatory printer licenses

prior censorship

state-controlled presses

church indexes of banned books

arrests, fines, and executions

Just as governments now pressure platforms to moderate content or suppress undesirable speech, early modern authorities attempted to reassert control over the runaway information economy.

The instinct is perennial: information escapes; power reacts.

5. The Long Arc: Chaos First, Enlightenment Later

Eventually the press stabilized into a mixed ecology:

the spread of mass literacy

the birth of newspapers

scientific treatises and mathematical works

philosophical movements

the Enlightenment

the scientific revolution itself

But the trash never disappeared. Modern bookstores still overflow with tabloids, pseudoscience, diet fads, and horoscope annuals.

The lesson is clear: democratized knowledge platforms do not uplift humanity uniformly. They amplify human nature—its brilliance and its stupidity.

The printing press gave us both Newton and Nostradamus almanacs. The internet gives us both arXiv and OnlyFans.

6. The Axio Lens: Chaos, Coherence, and the Pattern of Information Technologies

From the Axio perspective, the printing press is an early, slower instantiation of the Chaos Reservoir becoming widely accessible. A civilization’s informational substrate expands abruptly, making new patterns available but overwhelming existing Coherence Filters.

Early in the cycle:

Chaos outpaces Coherence.

Institutions lack the interpretive machinery to filter the flood.

Noise dominates signal.

Established authorities panic.

Only later do new filters emerge—scientific norms, peer review, constitutional protections, and specialized institutions of knowledge curation. Coherence catches up, never fully suppressing Chaos but balancing it.

The internet sits in the same transitional epoch Gutenberg’s Europe endured: an explosion of Chaos before the maturation of new filtering standards. We are not witnessing decline; we are living through the predictable turbulence before stabilization.

Conclusion

The printing press never delivered a pure Enlightenment. It delivered everything: genius, propaganda, scholarship, superstition, scientific revolution, fanaticism, erotica, and mass literacy all at once.

The internet’s current state is not a failure relative to its ideals. It is simply the early Gutenberg phase of a vastly accelerated media cycle. A world where universal knowledge is accessible but unevenly used is not the betrayal of the dream—it is the recurring human pattern whenever Prometheus hands us fire.