The Presumption of Innocence

Why extrajudicial killing is barbarism dressed as justice

September 07, 2025

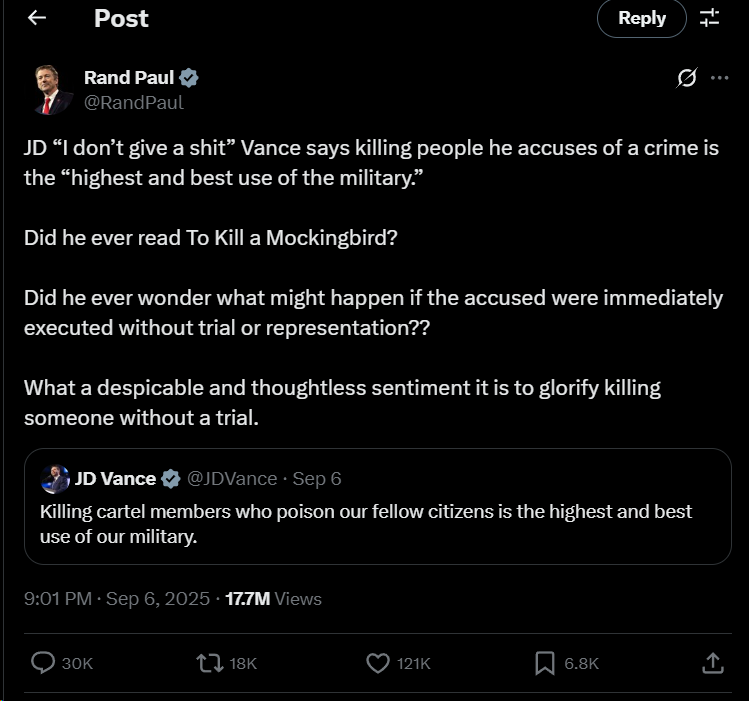

JD Vance’s claim—that killing cartel members is the “highest and best use” of the military—assumes something impossible: that guilt can be known with certainty prior to judgment. His mistake is not just political, it’s epistemological. It collapses the distinction between accusation and proof, suspicion and certainty, intelligence and truth. Civilization itself was built to prevent exactly this collapse.

1. The Problem of Knowledge

No agent, whether individual or institutional, ever has direct access to “guilt.”

Intelligence is inference. Surveillance, informants, and reports provide probabilistic signals, not guarantees. Human error, bias, and misinformation infiltrate every layer.

Accusation ≠ Truth. Treating suspicion as conviction is the hallmark of mob justice.

Epistemic humility is the recognition that we might be wrong. This humility is not weakness; it is the foundation of justice.

The deeper point: knowledge of guilt is never absolute. Every assertion of certainty is in fact a credence—a subjective probability—disguised as fact. Rule of law exists to prevent men with guns from confusing the two.

2. The Function of Trial

A trial is not bureaucratic red tape. It is an error-filtering mechanism built into the structure of justice.

Cross-examination dismantles unfounded claims.

Defense lawyers provide alternate narratives, forcing the prosecution to prove its case beyond reasonable doubt.

Rules of evidence expose unreliable witnesses and faulty data.

Public record ensures accountability, making it harder for abuses to vanish into shadows.

Without this machinery, executions become indistinguishable from lynchings. The difference between law and vengeance is the space for doubt.

3. Historical Lessons

History is filled with reminders of what happens when accusation equals guilt:

Salem witch trials: spectral evidence and rumor condemned innocents to death.

The Red Scare: suspicion of association destroyed reputations and livelihoods without proof.

Drone strike programs: the U.S. often defined a “military-age male in a strike zone” as a combatant by default. The error rate was hidden behind classification, but later evidence showed many of the dead had no ties to terrorism.

Each case shows how fragile truth is when filtered through power. Innocents die, trust erodes, and violence metastasizes.

4. Agency and Conditionalism

Measure vs. Credence: what we take as objective truth is never fully knowable; belief is always conditional. Vance’s position is the error of mistaking credence for certainty.

Conditionalism: all claims of guilt are conditional upon background assumptions and interpretations. Trials are the societal machinery designed to drag those conditions into the light.

Agency: to preserve agency, we must leave room for error. Killing based on suspicion annihilates not just individuals, but the possibility of correction. It forecloses futures that might have revealed innocence.

5. Why Rule of Law Is Sacred

Rule of law is not sacred because of tradition. It is sacred because it encodes epistemic modesty into the exercise of violence. It forces the state to admit: we might be mistaken.

Vance’s view collapses into authoritarian certainty: that the state knows who is guilty without needing proof.

Paul’s rebuttal defends institutionalized humility: that before the state can take a life, it must submit its claim to public scrutiny.

This is the true “highest use” of institutions—to keep our worst impulses restrained by the recognition of our own fallibility.

The essence of civilization is not that we punish the guilty, but that we refuse to kill the possibly innocent. Rule of law is the formal recognition that guilt is never self-evident, that certainty belongs to gods, not men. To abandon it is not strength, but barbarism.