The Trolley Problem

What We Miss When We Pretend It’s Just About Five Versus One

August 21, 2025

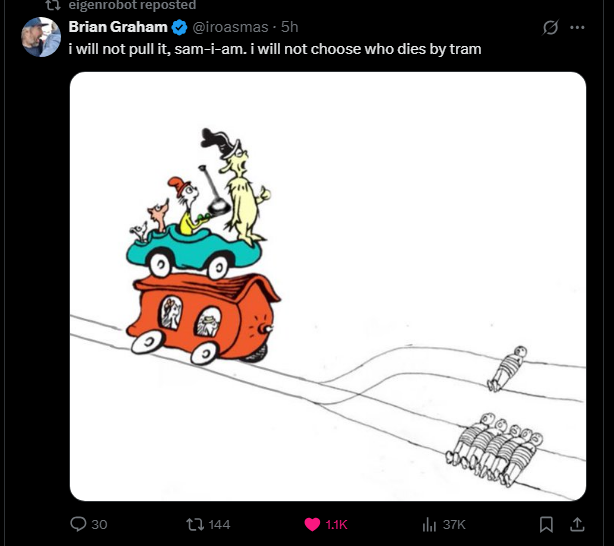

The Trolley Problem is usually presented as a sterile moral riddle: a runaway trolley will kill five people unless you pull a lever to divert it, in which case it will kill one. Do you intervene? Textbooks frame this as a test of moral theory—utilitarianism versus deontology, doing versus allowing, killing versus letting die. But that familiar framing leaves out critical insights. Once we press on the assumptions, the problem becomes far richer.

1. Premises as Game Rules

A common complaint is that the trolley scenario is unrealistic: why only two options, why no other interventions? But thought experiments are games, and the rules are their premises. Complaining about unrealistic constraints is like objecting that pawns in chess don’t move like real soldiers. The artificiality is intentional. It’s meant to force clarity about principles under conditions of extreme abstraction.

Where things get interesting is not that the rules are unrealistic, but that they encode hidden assumptions. When philosophers set up the trolley puzzle, they smuggle in a specific metaphysics of agency: binary options, a single central agent, an isolated moment of choice. These may be unrealistic, but they are still telling. The problem is designed not to mirror life, but to spotlight certain tensions.

2. Action, Inaction, and the Default Path

A deeper asymmetry lies in the difference between intervening and allowing the default. If you are unaware of the trolley, the default outcome is five deaths. Once you become aware, you can:

Act as if unaware: let the default continue.

Intervene: redirect the trolley, taking responsibility for one death.

Both choices are causal under any rigorous definition. Doing nothing is not absence of causality; it is choosing the world’s preloaded trajectory. The real asymmetry is not causal versus non-causal, but default versus intervention. One path corresponds to how the world proceeds without you. The other path requires inserting yourself into the chain of events.

This is why the Trolley Problem resonates. It is not fundamentally about arithmetic of lives, but about whether awareness obligates intervention. Do we accept the default or override it? This is the real crucible the puzzle reveals.

3. Beyond the Lever: Consequences That Matter

The standard discourse stops at counting lives. But in reality, consequences extend far beyond that moment:

Legal: If you pull the lever, you’ve acted directly to kill one person. In many systems that’s prosecutable homicide. Doing nothing, by contrast, rarely creates legal liability.

Social: The family of the one will see you as a murderer. The families of the five may defend you, but public perception often gives more moral weight to active harm than to omission.

Psychological: If you intervene, you must live with the guilt of having chosen a death. If you don’t, you carry the guilt of inaction. The difference lies in which kind of guilt is bearable.

Strategic: If interveners are punished, society trains itself to prefer inaction. A precedent of punishing intervention skews the equilibrium toward universal passivity.

Once we include these layers, the five-versus-one arithmetic collapses. Rational agents may conclude it is safer—legally, socially, psychologically, strategically—to let five die rather than intervene.

4. The Agent-Relative Turn

And yet, this isn’t the whole story. Suppose the five are strangers and the one is your child. Or the inverse: the one is a stranger, the five are your family. The tidy utilitarian calculus disintegrates. Real human valuation is not impartial. We weight family, tribe, loyalty, and bonds more heavily than strangers. Value is not fungible across persons.

Moreover, your own survival matters. If pulling the lever saves five strangers but guarantees you a life sentence, the effective equation is not 5 vs. 1. It is 5 vs. 1 + you (and the costs your imprisonment imposes on your family). That flips the balance for most rational agents. But if those five are your family, many of us would still pull—accepting personal destruction to preserve them. That’s not utilitarian arithmetic. That’s agent-relative valuation.

5. What the Trolley Really Tests

The trolley problem, stripped to its bones, doesn’t reveal who is a utilitarian or a deontologist. It reveals:

Do you treat awareness as an obligation to intervene, or as a fact you can bracket away?

Do you prioritize impartial arithmetic, or partial bonds?

Do you value abstract outcomes above your own legal, social, and psychological survival?

Can you live with omission-guilt, or commission-guilt?

It is less a puzzle of moral theory than a probe into how we handle defaults, responsibility, and value.

Conclusion

The familiar discourse around the Trolley Problem misses the point. It isn’t just a bean-counting game. It is a compressed model of the real dilemmas of agency: whether to accept or override the default, how to weigh downstream consequences, and how to balance impartial and agent-relative values. The real question is not “five or one?” but: What are you willing to risk, suffer, and sacrifice, and for whom?